Content harmful to minors: Fines imposed by the National Broadcasting Council

The number of decisions by the chairman of Poland’s National Broadcasting Council imposing fines on media service providers for broadcast violations has risen dramatically over the last five years. These decisions involve content standards (respect for law, public order, morality, religious beliefs), protection of minors, and improper language. In 2011–2018, an average of three decisions imposing fines on providers were issued per year. Between 2019 and 2023, this figure leapt fourfold, to an average of 12 per year, and in 2023 there were more than 20. Fines for content harmful to minors are particularly noteworthy for their frequency and problematic nature.

Legal basis

The media in Poland are not treated equally in oversight of the content they distribute. While broadcasters (radio or TV) and VoD providers have been subject to specific obligations for years, the requirements for other providers are limited. This is especially true for online video sharing platforms and social media, where liability is only now taking shape, based mainly on a new chapter added to Poland’s Radio and Television Act in 2021 regulating video-sharing platforms, and the Digital Services Act (Regulation (EU) 2022/2065), which recently entered into force.

Strictly speaking, the content rules imposed on broadcasters and VoD providers constitute a form of censorship, i.e. restrictions on the freedom of speech guaranteed by the Polish Constitution and the European Convention on Human Rights. But this censorship is justified under the applicable laws in particular by the need to protect health and morals, as well as the rights and freedoms of other persons.

Oversight of content distributed by television, radio and video streaming is exercised in Poland by the chairman of the National Broadcasting Council (KRRiT), who issues decisions based on the RTV Act. Under the EU’s country-of-origin principle, the RTV Act applies to media service providers and video-sharing platforms established in Poland. (This jurisdiction arises from implementation of an EU directive, with a complex method to determine whether a supplier is established in Poland, but the decisive criteria are the provider’s registered office, where editorial decisions are taken, and the location of programming staff—but mere location in Poland is not enough to regard the provider as established in Poland.)

The RTV Act sets certain content requirements for broadcasts. The rules on protecting minors from harmful content can be grouped as follows:

- Provisions absolutely banning certain broadcasts due to content endangering the development of minors (in the case of “linear” (scheduled) radio and TV programming) or requiring technical or other measures preventing minors from accessing them (in the case of “non-linear” programming—i.e. VoD (“on-demand audiovisual media services”))

- Provisions banning the distribution of broadcasts but only within a certain timeframe—these include “adult-only” broadcasts, which can be aired only between 11 pm and 6 am, and broadcasts permitted for ages 16+, which can be aired after 8 pm

- Rules requiring providers to classify broadcasts and use age-appropriate designations.

In addition to the RTV Act, the KRRiT regulation of 13 April 2022 on programming that may have a negative impact on the development of minors, which came into effect on 1 May 2022 (replacing an earlier regulation from 2005), applies in this area.

Protection of minors: Classification and designation of content

In principle, the obligation to classify broadcasts and designate them appropriately applies to all content, regardless of its subject matter or the degree of potential harm to the development of minors. Only the following are excluded:

- News programmes

- Advertising

- Telemarketing

- Sports broadcasts

- Text (e.g. electronic programme guides, but not text in chyrons (information bars occupying part of the screen during a broadcast)).

Therefore, a media service provider will not escape a fine even if it distributes only innocuous content intended for all viewers (even young children), but does not designate it with the correct symbol throughout the broadcast. But in practice, in such cases the regulator has imposed relatively mild fines of about PLN 2,000 per violation found during spot checks.

The rules for classification and symbols that must be used by media providers are set forth in the KRRiT regulation of 13 April 2022.

Banned content

Some programming may not be broadcast at all, at any time. This ban applies to content endangering the physical, mental or moral development of minors, in particular containing pornography or gratuitous violence. Such items cannot be aired at all (regardless of the time) on linear radio or television. In the case of non-linear (VoD) services, the RTV Act requires the use of technical or other measures preventing minors from accessing such content. In practice, VoD providers use various “parental protection” tools in this regard (e.g. an obligation to provide credit card details or pay electronically). Notably, in this regard VoD providers in Poland have self-regulated through the adoption in 2014 of the Code of Best Practice on Rules for Protection of Minors in On-Demand Audiovisual Media Services, updated in 2022. Monitoring by the National Broadcasting Council has found a high level of compliance with the code.

Adult-only content

A certain set of broadcasts are classified as allowed exclusively for adults. These are broadcasts that may have a negative impact on the physical, mental or moral development of minors. Such programming may only be aired between 11 pm and 6 am, and on television must be accompanied by the following designation:

In addition to the white key on a red background, content allowed from 18 years of age containing violence (przemoc), sex (seks), obscenities (wulgaryzmy) or references to narcotics (narkotyki) must be accompanied by a graphic of the initial identifying the type of the content:

Other programming

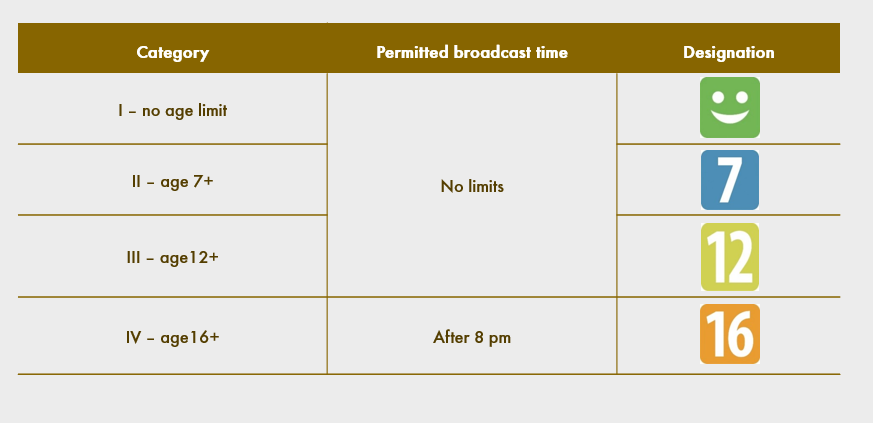

Other content may be shown to minors, but the regulations divide them into four age categories, reflecting criteria relevant to the development of minors (e.g. worldview, moral judgments, emotional response, and behavioural patterns):

But the wording of the RTV Act and regulation is value-based and open to ambiguity, so the regulator’s practice is crucial for interpretation.

Protection of minors: regulatory practice

The regulator’s decisions on harmful content offer a valuable source of knowledge on the types of content and method of distribution that will be found to violate the law. Some examples of rulings discussed below help convey the regulator’s approach in this area.

Banned content

In last five years, the decisions by the chairman of the National Broadcasting Council on banned content have involved pornography and gratuitous violence.

Pornographic content

The law does not define pornography. In its judgment of 23 July 2010 (case no. IV KK 173/10), the Supreme Court of Poland defined “pornographic content” as the presentation of human sexual activities (especially the display of sexual organs in their sexual functions), whether or not the activities presented are consistent with socially accepted patterns of sexual behaviour. The court explained that the essence of pornography is conveying specific content, and not just recording of a specific event.

Polish legal scholars have also attempted to define pornographic content. The best-known definition, proposed by Prof. Marian Filar, identified the following characteristics of pornographic content:

- Presentation of manifestations of sexuality and human sex life

- An exclusive focus on technical aspects of sexuality and sex life, disconnected from the intellectual and personal layer

- Presentation of human organs in their sexual functions

- Primarily intended to cause sexual arousal in the recipient.

In its judgment of 11 July 2017 (case no. VI ACa 2026/15), the Warsaw Court of Appeal cited these criteria, while noting that they only help exemplify pornographic content, and the film challenged in that case did not have to meet all of those criteria to be deemed pornographic.

The chairman of the National Broadcasting Council agrees with this approach of the court of appeal. When classifying content as pornographic, the regulator emphasises its main purpose, i.e. to cause sexual arousal in the recipient. This in turn is determined primarily on a cumulative basis, depending on the degree of realism of the scenes of sexual interactions, characteristic movements and facial expressions of people shown in the broadcast, as well as the soundtrack (lewd noises and crude vocabulary). Examples of films found by the regulator to be pornographic include My Father’s Secretary (dir. Frank Major, 2017), Les filles de la campagne (dir. Hervé Bodilis, 2010), In the Army Now (dir. Daniel Petrie, 1994), 40 Ans, mariée mais libertine (dir. Kendo, 2014), and Les filles de Madame Eva (dir. Alis Locanta, 2018).

It seems that in practice, whether a film is deemed “pornographic” (i.e. banned from broadcast altogether) will depend on the accumulation of risqué scenes, how each scene plays out, and their total duration. Indeed, in principle images of naturalistic sex or pathological forms of sexual life (e.g. violent or non-consensual) can be broadcast on television in Poland, but are relegated to the graveyard shift between 11 pm and 6 am. The higher the proportion of sexual content (usually more than 50% of the total film), the flimsier the plot (only a pretext for sexual content), and the scantier the dialogue, the greater the risk that the film will be deemed pornographic.

Gratuitous violence

The regulator has found the films Women of Mafia and Women of Mafia 2 (dir. Patryk Vega, 2018–2019) to be unsuitable for broadcasting on television due to excessive exposure to violence.

This is understood as focusing the message on violence and accentuating it, e.g. by using closeups or other visual effects or repeatedly showing aggression in different variants. In assessing whether the violence is warranted, artistic aspects of the broadcast (e.g. the fictional plot) are taken into account, as well as society’s informational interests (when reporting true events). But it is recognised that showing extreme images for the purpose of cheap sensationalism or to gratify unhealthy curiosity should always be avoided.

The grounds for regarding the violence in Vega’s mafia films as excessive were primarily the nature of the scenes (drastic depiction of torture, mutilation, rape and murder). The depictions were not justified by the plot or the characterisations, even taking into account the creators’ vision of portraying the criminal underworld. And the individual acts of violence were meticulously depicted, with great intensity. Numerous scenes of violence were not limited to settling the score between offenders, but side plots, irrelevant to development of the action, were also infused with brutality. According to the regulator, these scenes served only to showcase extremely brutal, refined and sadistic techniques for inflicting suffering and death. The message focused on violence, but gratuitously from the point of view of the meaning or artistic considerations. Thus the films were deemed to pose a direct threat to the development of underage viewers.

Excessive exposure to violence can occur not only in cinematic fiction, but also in documentaries or news broadcasts. An example is an episode from the investigative TVP show Alarm! with footage of a man deliberately driving several times over a dog lying on the road. The drastic scenes, including crushing the dog’s head with its mouth wide open, intensified by the soundtrack of the abused animal whimpering, were clearly shown, without employing any techniques for blurring the image or muffling the sound. Thus the broadcast violated Art. 18(4) of the RTV Act.

Adult content

This is a category where content is not banned outright. The case law (e.g. Warsaw Court of Appeal judgment of 10 June 2008, case no. VI ACa 1555/07) recognises situations where the hazards posed by questionable content are “possible” in the sense of “likely,” where it is sufficient that the content could have a negative impact on the normal development of minors (physical, mental or moral), as opposed to banned content, where the threat has been established (actually exists).

The chairman of the National Broadcasting Council pays a lot of attention to broadcasts containing violence and depicting sexual pathologies, which were erroneously classified as “16+” (instead of “18+”) and aired after 8 pm (and not after 11 pm). It is assumed that minors age 16–18 may take a simplistic approach to resolving complex existential issues, and thus internalise scenes justifying violence as a defence against dangers, or treat physical attractiveness and sexual abandon as a marker of success in life. The regulator takes the view that under the influence of such images, viewers come to see these phenomena as normal, or become indifferent to them, but in minors this can disrupt their moral development and blur the distinction between right and wrong.

In deeming physical violence unsuitable for minors, the regulator takes into account the brutality of the scenes, their length and frequency, the method of depiction (e.g. precise closeups), and whether aggression is condoned or justified in the programming. The mere fact that a film has taken on cult status in cinematography does not justify showing it during the protected time (between 6 am and 11 pm).

In this regard, an example is the celebrated film Pigs (dir. Władysław Pasikowski, 1992), which on several occasions has been subject to decisions by the chairman of the National Broadcasting Council. In this film about former communist secret police, the numerous scenes of physical violence, portrayed brutally and naturalistically—such as torture, murder, drowning of bodies, splattering blood, finishing off wounded victims, brutal beatings, pouring liquid from a canister over a victim, shooting victims in the head with a machine gun, showing a bloody body and mutilated body parts (such as gouged-out eyes or body parts dangling after a shooting)—have led to decisions finding that the film is not suitable for showing to minors. The protagonists of Pigs display violent behaviour patterns and use vulgar language, making them a negative role model for underage viewers.

The regulator reached a similar conclusion on Rambo: Last Blood (dir. Adrian Grünberg, 2019), holding that showing the film before 11 pm with the designation “16+” also violated Art. 18(5) of the RTV Act. The authority found that the long, suggestive scenes of violence in the film, with close camera shots—such as sticking a knife into a body, strangulation, pressing a finger into a wound, the sound of body tissue being torn apart, battering the victim with a hammer, slitting the victim’s throat, driving a rod into the victim’s head, cutting off limbs, cutting out the heart, showing a bloody, headless body, throwing a bleeding head, throwing an axe so it is embedded in the victim’s head—are not suitable for minors, even if the main character is driven by a noble motive of saving a family member in distress.

Similar rulings were reached for the broadcast of such films as John Wick: Chapter 3—Parabellum (dir. Chad Stahelski, 2019), Pitbull (dir. Patryk Vega, 2021), The Raid 2: Retaliation (dir. Gareth Evans, 2014), Deadpool (dir. Tim Miller, 2016), and Amok (dir. Kasia Adamik, 2017).

Such naturalistic, brutal depictions of physical aggression may be contrasted with another film relegated to the “18+” category, Mall Girls (dir. Katarzyna Rosłaniec, 2009). That film depicts scenes of fights between girls (hair-pulling, shoving a girl’s head in the toilet), a girl being slapped by her mother and jerked about by her father. These might seem tame compared to the aforementioned scenes of mutilated body parts, torture and so on, but violence was only the icing on the cake in assessing the overall tone of Mall Girls. The key to its “18+” rating was the depiction of sexual pathologies, detached from lofty emotions, reducing human relations to a primitive sexual level (prostitution of underage girls with much older men), accompanied by images of aggression aimed at humiliating the battered victim. The movie is drastic and suspenseful, and the scenes could harm minors by forming in them false ideas about human relations and sexuality. According to the regulator, to guard against inappropriate reception of this kind of content, viewers first need to have an established system of values as a counterweight to the world presented in the film. This meant that Mall Girls, although a film about teenage girls, was intended only for adults.

Botox (dir. Patryk Vega, 2017), containing numerous scenes of drunken carousing, and pathological behaviour such as stealing from the dead, bestiality, or insertion of foreign objects in orifices, was met with similar allegations by the chairman of the National Broadcasting Council. The film also depicts positive sensations after drug use, scenes of masturbation, and sexual exploitation of an unconscious woman. The regulator singled out the film’s refusal to stigmatise inappropriate behaviour, even endorsing it.

The US reality TV series Dating Naked (2014–2016) was also deemed inappropriate for Polish youngsters. In the show, participants go about seeking a life partner while they are entirely naked (although their genitals are pixelated). It was alleged that the show depicted distorted forms of social coexistence and undesirable patterns of behaviour, e.g. judging a person’s worth as a potential partner based on the attractiveness of certain body parts and portraying a lack of moral or sexual inhibitions as increasing the chance of winning the competition. According to the chairman of the National Broadcasting Council, the lewdness of the broadcasts promoted sexual stereotypes and objectification. If minors saw the show, they might assimilate these views, as young viewers tend to regard images created by the media as a faithful representation of reality.

Other content

Infractions have also been found in content “not just for adults.” In addition to the lack of age designations during broadcasts, this mostly applies to broadcasts distributed with a milder age designation, when they should have been aired after 8 pm with the “16+” designation.

Thus, for example, the regulator found that the broadcast of a music video by the band Weekend entitled “Wypijemy, popłyniemy” [roughly, “We’ll drink and swim”] shortly before 4 pm in a music programme with the designation “12+” violated Art. 18(5b)(1) of the RTV Act, as the content was not suitable for minors under the age of 16. This was because the content approvingly portrayed risky, health-threatening behaviour, such as drinking while driving, and depicted alcohol as an element of a successful party, along with a simplified view of the world reduced to eroticism.

Similarly, according to the regulator, What Planet Are You From? (dir. Mike Nichols, 2000) was improperly broadcast around 1:30 pm, based on a finding that the movie’s plot, involving an alien mission to impregnate female earthlings, was inappropriate for children as young as 12. The film might promote obscene vocabulary and perpetuate unacceptable behaviour in the form of treating earthlings as sex objects.

Sanctions practice

The chairman of the National Broadcasting Council has the duty to punish a broadcaster or VoD provider that has broken the rules on harmful content, by imposing a fine. In extreme cases, a broadcaster may have its licence revoked, or a VoD provider may be removed from the list of on-demand audiovisual media services, making it impossible to continue legally offering a given media service.

But it is standard practice for the regulator to apply sanctions in the form of fines. The regulator can waive a fine and merely caution the broadcaster if the gravity of the violation is negligible and the party has ceased the violation, but in practice this is rare. A fine cannot be imposed more than one year (in the case of a broadcaster) or two years (in the case of a VoD provider) after the violation.

The fine can be up to 10% of the broadcaster’s revenue from the previous fiscal year, or, as the case may be, up to 50% of the annual fee for the rights to the frequency used by the channel (if the violation occurred there). As for VoD providers, the fine may not exceed 20 times the average monthly salary in the enterprise sector, as announced by Statistics Poland.

In imposing a fine, the regulator must consider:

- The extent and severity of the violation

- Previous activities of the entity (whether it has been fined before for violating the RTV Act, and if so, which provisions)

- If the case involves a broadcaster (not a VoD provider), its financial capabilities are also taken into account (based on a review of its financial statements).

In practice, fines imposed by the regulator for broadcasting content harmful to minors at the wrong time or with the wrong age rating usually fall within the range of PLN 15,000–30,000 per incident, although higher sanctions are sometimes meted out (c. PLN 70,000). Relatively modest sanctions (c. PLN 15,000) may also apply to banned content, particularly when late in the day—often after midnight, so actual access by minors was significantly limited.

Summary

An analysis of the decisions of the chairman of Poland’s National Broadcasting Council issued in recent years shows that the content of broadcasts aired by the media is an important concern of the regulator. This does not seem likely to change, especially considering the increased discussion of the need to protect minors from harmful content, particularly on the internet.

At the same time, when drawing up a broadcast schedule, media service providers must fill the allotted time and ensure that the schedule is attractive to audiences—increasing the risk of error and exposure to fines. Thus it is vital, to protect their own interests, that broadcasters and VoD providers keep abreast of the regulatory practice.

Barbara Załęcka-Wysocka, attorney-at-law, patent attorney, Intellectual Property practice, Wardyński & Partners