New provisions on by-products

The amendment to the Waste Act which is to come into force at the beginning of 2022 implements the amended Packaging and Packaging Waste Directive into the Polish legal system and constitutes a step towards a circular economy. One of the more significant changes relates to by-products.

By-products are substances or objects resulting from a production process whose original purpose is not to produce them. If certain conditions are met, such materials may be traded and managed as by-products rather than waste. This classification allows businesses to use and trade in by-products while bypassing stringent waste management requirements.

However, to ensure that these materials do not pose a threat to the environment and human health, they must meet the requirements enabling their further use in accordance with the law. The EU regulations and the Waste Act in Poland have determined that such materials must meet the following criteria to be considered a by-product:

- Their continued use is certain

- They may be used directly without any further processing other than normal industrial practice

- They are produced as an integral part of the production process

- They meet all important requirements including legal, product, environmental and human life and health protection requirements for the specific use of these substances or objects, and such use will not lead to overall adverse environmental or human life or health impacts.

From tacit approval to marshal’s decision

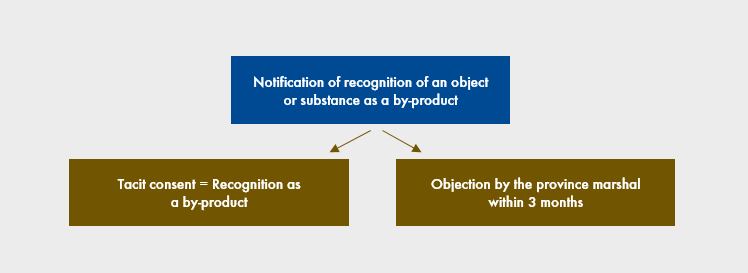

Originally, from the time the 2012 Waste Act came into force, the procedure for recognition as a by-product was relatively straightforward. The manufacturer of an object or substance resulting from a production process, the primary purpose of which is not their production, was required to submit to the province marshal a notification of recognition of the object or substance as a by-product. The notification had to be accompanied by evidence of compliance with the statutory requirements. An object or substance was recognised as a by-product if the province marshal did not object by issuing a decision within three months of receiving the notification. Thus, the positive effect for the manufacturer arose as a result of the tacit consent of the administrative body.

Fig. 1. Procedure for recognition of a by-product under the law in force 23 January 2013 – 28 August 2018

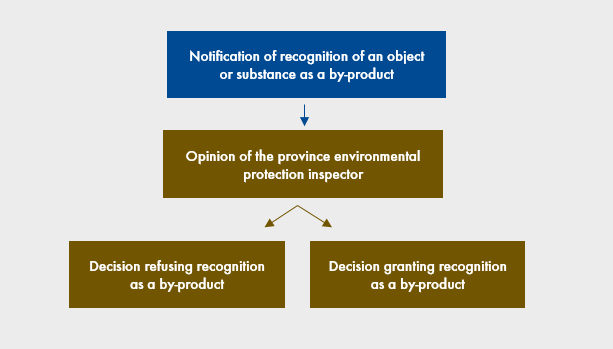

In 2018, this procedure was modified. Under the new provisions, recognition or refusal to recognise an object or substance as a by-product required each time the activity of the province marshal by way of a decision issued after administrative proceedings initiated by the manufacturer of the material which was to be considered a by-product. Thus, the possibility of recognition of a by-product by tacit consent was eliminated. The changes introduced by the amendment were only procedural: the parliament neither modified the conditions for recognition of a by-product nor changed the formal requirements regarding the content of the notification.

Before issuing a decision, the marshal had to consult the province environmental protection inspector. Before expressing an opinion, the inspector could inspect the notification. The inspector’s negative opinion obliged the marshal to issue a decision denying recognition as a by-product. In the event of a positive opinion, the marshal could issue a decision either recognising the object or substance as a by-product or refusing to recognise it as a by-product. A positive decision was issued for a fixed period, not exceeding 10 years.

Fig. 2. Procedure for recognition of a by-product under the law in force 29 August 2018 – 31 December 2021

Additionally, the 2018 amendment contained a provision under which recognition of an object or substance as a by-product prior to enactment of the amendment expired six months after that date. Businesses benefitting from previous recognition of by-products on the basis of the marshal’s tacit approval had to renotify the object or substance as a by-product to continue to benefit from this solution.

Systemically, this solution was not understandable, as the amendment did not modify in any way the prerequisites for recognition as a by-product or the formal requirements allowing filing of notification. Therefore, businesses had to refile an identical notification and demonstrate again that the same conditions were met. The relatively short transitional period of six months after which recognition as a by-product expired meant that a new notification had to be submitted immediately in order to obtain a positive decision before the prior recognition expired. However, the administrative proceedings took a long time, province inspectors often issued negative opinions on notifications, and such opinions were appealed against to the Chief Inspector of Environmental Protection. Meanwhile, recognitions of by-products were expiring, and businesses had to treat production leftovers as waste until a positive decision from the marshal was obtained. At the same time, “treatment as waste” is not just a minor formality, but requires obtaining certain permits and approvals, entries in registers, record-keeping and reporting. In many cases, the proceedings for recognition as a by-product continue to this day, although more than three years has passed since the amendment came into force.

As mentioned, the point of amending the provisions was not systemically defensible with regard to existing by-products, as the amendment did not change the conditions for recognition as a by-product nor the requirements regarding the content of the notification. The rationale behind the new legislation implied that there was a risk that marshals would not raise objections to certain substances and objects, which could result in erroneous recognition of hazardous materials as by-products when instead they should be classified, for example, as hazardous waste. In turn, the lack of proper classification resulted in such materials being used without stringent waste management requirements. However, it is hard to avoid the impression that in practice, businesses have borne collective responsibility for potential mistakes by public officials. Instead of introducing the possibility of targeted verification of notifications, lawmakers made all interested parties reapply.

A third approach to by-products

As of 1 January 2022, we face another significant change in the provisions regarding by-products.

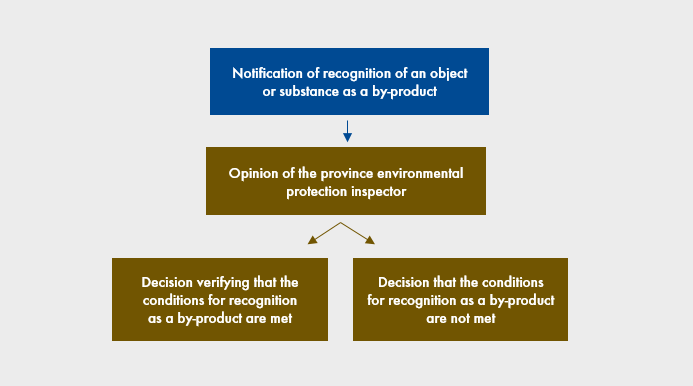

Fig. 3. Procedure for recognition as a by-product from 1 January 2022

The biggest difference is that an object or substance meeting the conditions qualifying it as a by-product will be a by-product by virtue of law. The marshal’s decision will only confirm this. Now, by contrast, until it obtains a marshal’s positive decision, the manufacturer has had to classify the notified material as waste.

The catalogue of conditions for recognition as a by-product has been clarified by indicating that specific conditions for recognition as a by-product must also be met, if such conditions have been defined in EU law or in implementing regulations to the Waste Act.

In view of the declaratory nature of the decision issued by the marshal, from 2022 this body will issue a decision confirming that the conditions for recognition as a by-product have been met or a decision finding that those conditions have not been met. The decision will still be issued for a specified period, not longer than 10 years, after consultation with the province environmental protection inspector. As before, a negative opinion of the inspector will oblige the marshal to issue a decision finding that the conditions for recognition as a by-product have not been met.

More doubts than clarity

While recognition of objects or substances as by-products by virtue of law is a great convenience for businesses, the other solutions coming into force at the beginning of 2022 raise numerous doubts.

First, the changes appear to go the opposite direction of the previous amendment. As mentioned, the previous change was justified by the need for greater control over the process of recognising materials as by-products, as there was a risk that the marshal’s passivity, i.e. “tacit consent,” could result in recognition of, for example, hazardous waste as a by-product. But from 1 January 2022, obtaining a marshal’s decision will not be a condition for recognition as a by-product at all.

Second, a consequence of the mechanism adopted in the amendment is that businesses will be able to benefit from recognition of a given material as a by-product even before the marshal issues a decision. Therefore, the question arises why such a decision should be obtained at all, if it is only confirmatory in nature. Undoubtedly, it will remain the responsibility of the manufacturer of the object or substance to obtain such a decision, as the amendment did not change Art. 11(1) of the Waste Act, pursuant to which the manufacturer of an object or substance is required to submit a notification of recognition of the object or substance as a by-product to the province marshal for the place of production. However, the provisions do not establish any sanctions for breach of this obligation. Previously, the absence of a decision by the marshal meant that the manufacturer could not enjoy the benefits of recognition as a by-product. Dropping this effect means that businesses may no longer have an interest in obtaining a marshal’s decision.

Third, it may be argued that the marshal’s decision increases the certainty of trade, as a business classifying post-production residue as a by-product rather than waste will not be exposed to the risk of challenge to its applied practices, for example in the course of an inspection by the province environmental protection inspector—as it will be in possession of a marshal’s decision confirming the correctness of its classification of the by-product. However, such security may be illusory, as the marshal’s decision confirming that the conditions for recognition as a by-product are met concerns a strictly defined object or substance created in a given production process, and use of such a decision is only certain within a defined production process of the recipient of the decision. Therefore, administrative bodies will still be able to question the correctness of the classification as a by-product, claiming that the positive decision of the marshal was issued on the basis of the state described in the notification, which may differ from the actual management of the object or substance by the business.

Fourth, since the marshal’s decision is to be merely a confirmation that the conditions have been met, it is unclear why the provision that the decision is to be issued for a specified period, not longer than 10 years, has been retained. Expiration of this period will not render the by-product waste again, but the producer of the by-product will no longer be able to benefit from the finding that its classification of the material is correct.

The coming months are likely to see many disputes over the classification of certain products or substances as by-products. It can be expected that certain practices will be challenged by administrative bodies and the environmental inspectorate. If their objections are upheld, businesses managing materials erroneously recognised as by-products without observing the rigours of the waste legislation may face severe sanctions.

Dr Dominik Wałkowski, adwokat, Environment practice, Wardyński & Partners