How does access to public information work in Poland?

Disputes over access to public information are increasingly finding their way onto the court docket in Poland. Higher public awareness and a desire for citizen oversight of issues of particular public interest may be the reason. But administrative authorities or other entities obliged to provide information, whose decisions are subject to further review, often refuse to provide the requested information. What is public information, how to obtain it, and what to do when access is denied?

What is public information?

Access to public information in Poland is governed by the Access to Public Information Act of 6 September 2001. Under the act, any information regarding public affairs is public information. This type of data may relate, in particular, to domestic and foreign policy, entities performing public tasks and their rules of operation, official documents, as well as public assets.

The catalogue of information that can be obtained is extensive, as access is limited essentially by two conditions:

- Privacy of a natural person (this does not apply to information on persons holding public functions, related to performance of such functions)

- Business secrets.

The wide range of data that can be requested arises from the constitutional right to public information, which furthers one of the fundamental values in a democracy—the transparency of public institutions.

Another restriction exists, not explicitly stated in the act. It is not possible to obtain public information in one’s own case, as these issues relate to an individually identified person (this view is well established in the case law, e.g. Supreme Administrative Court judgment of 14 July 2020, case no. I OSK 2817/19, Lex no. 3034920). The procedure for obtaining information on these matters is set forth in other laws, such as the Civil Procedure Code and the Administrative Procedure Code.

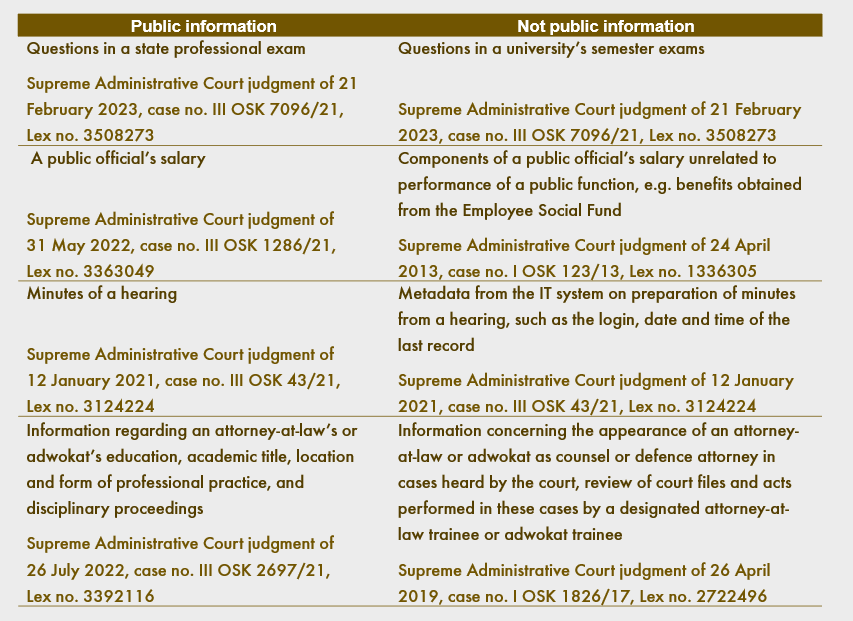

Sometimes, defining what is a public matter and what is not is debatable. Therefore, the boundaries of the concept of public information are often delineated by the courts on the basis of the specific facts.

How to obtain public information?

Anyone who is interested in obtaining public information may obtain it. The act provides for six methods for entities holding public information to release that information:

- Announcing it in the Public Information Bulletin

- Posting it in a publicly accessible place

- Installing a device in a publicly accessible place allowing persons to read it

- Allowing access to meetings of collegial public authorities (e.g. city council) and providing access to materials documenting such meetings

- Posting information on a data portal (run by the minister for information technology—a publicly accessible ICT system for making public sector information available for reuse and private data available for use, formerly the Central Repository of Public Information)

- Upon request.

Public information that can be provided immediately should be made available in oral or written form without a written request. Two factors determine when information can be made public immediately: first, whether it faithfully corresponds to the request in form and content; second, whether it is necessary to perform additional, time-consuming acts to find or prepare the information to meet the request (Province Administrative Court in Gliwice judgment of 2 September 2019, case no. III SAB/GI 219/19, Lex no. 2724970).

Request procedure

One of the more common methods to obtain public information is to file a request. This can be done in any form, as long as it is clear from the applicant’s request. So there is no obstacle to addressing an inquiry electronically (e.g. by email) or remotely using a trusted profile. In this regard, the act does not provide for any formal requirements. And it is not necessary to specify in the request the mode for release of the information, or to disclose a factual or legal justification for the request.

If on the other hand one would like to obtain the information in a specific form (e.g. as a scan of documents) or in a specific way (e.g. by email), this must be stated in the request. The entity obliged to provide access to information has to comply with the indicated manner and form of data transmission, unless the technical means at its disposal do not allow it to do so. In other words, if an applicant requests public information by email, the other party can refuse to provide access in this form only when it indicates that for certain technical reasons, the information cannot be sent by email. In this situation, the entity will notify the applicant in writing of the reasons for the inability to provide the information in that form, and inform the applicant how or in what form the information can be made available immediately. If a follow-up application for disclosure of the information in accordance with the notification is not submitted within 14 days of the notification, the procedure for disclosure of information will be discontinued.

It is also possible to request processed information, but then it must be particularly relevant to the public interest. Such information calls for public data first requiring analysis, calculation, a statistical summary, or an expert opinion. Carrying out these activities according to the criteria indicated by the applicant may lead to creation of a new document, but this is not always the case, as extraction of specific information from a collection of documents also constitutes processing. Unlike simple information, when requesting processed information, the applicant also has to demonstrate that the request is motivated by a particularly important public interest.

On this issue, a question often arises whether data that must be anonymised before being provided to the applicant constitutes “processed” information. In principle, anonymised data does not constitute processed information, as the anonymising involves conversion rather than processing (Province Administrative Court in Wrocław judgment of 9 March 2023, case no. IV SA/Wr 595/22, Lex no. 3516811). But if the anonymisation involves a particularly large amount of work, commitment of staff and resources, the results may be regarded as processed information (Province Administrative Court in Olsztyn judgment of 28 February 2023, case no. II SA/OI 687/22, Lex no. 3508260). This is justified, because complying with the request will disrupt the normal course of operation of the entity holding the data.

A request for public information is free of charge, unless the entity must incur additional costs for providing it. This concerns the need to process information or disclose the information in the form or manner indicated by the applicant.

Public information should be provided without undue delay, but no later than 14 days from filing a request. If the requested information cannot be provided within 14 days, then the entity must notify the applicant of the reasons for the delay and the expected date of disclosure (the deadline may be extended to a maximum of 2 months from filing the request).

Providing public information at the request of an interested party is a material and technical act of the entity and does not require issuance of an administrative decision. No additional documents authorising access to the information are needed. It is enough that public information is actually provided.

At the same time, an entity providing public information must allow it to be copied or printed, or potentially transmitted by a commonly used medium.

Negative decision—then what?

Refusal to provide public information or discontinuation of the proceeding constitutes an administrative decision (unlike when an entity grants a request for information). Such a decision should include:

- Name and address of the entity obliged to provide public information

- Date of issuance

- Name and address of the party or parties making the request

- Citation of legal basis

- Determination

- Factual and legal justification, and the names and functions of persons who took a position in the course of the proceeding seeking disclosure of information, as well as the name and address of entities in view of whose interests the decision to refuse the disclosure of information was issued

- Guidance on whether and in what mode the decision can be appealed, the right to waive an appeal, and the consequences of waiver

- Signature with the name and position of the employee of the entity obliged to provide public information authorised to issue the decision, and

- In the case of a decision against which an objection or complaint may be filed with the administrative court, guidance on:

- The admissibility of filing an objection or complaint

- The amount of the fee for filing a complaint or objection against the decision if it is a fixed fee, or the basis for calculating the fee if it is on a sliding scale

- The party’s right to apply for an exemption from costs or right to assistance.

The case law pays particular attention to the need for correct and comprehensive justification of a negative decision. In such a situation, the relationship between the documentation that would be subject to disclosure and confidential information that impinges on the operation, profitability or competitiveness of a business, or the need to protect the privacy of a natural person, must be adequately described.

The party may file an appeal against a negative decision, which should be examined within 14 days. If the body fails to meet this deadline, the applicant may file a complaint against inaction with the province administrative court. In that case, it is not necessary to file a reminder, as in other administrative proceedings for inaction or protracted proceedings (Supreme Administrative Court judgment of 24 May 2022, case no. III OSK 4146/21, Lex no. 3588905).

When considering the appeal, the body will issue one of four determinations:

- Uphold the appealed decision

- Set aside the appealed decision in whole or in part and discontinue the first-instance proceeding in whole or in part

- Discontinue the appeal

- Set aside the appealed decision and remand the matter for reconsideration.

In the first three cases, the applicant has a right to file a complaint with the province administrative court within 30 days of obtaining the decision. In the last situation, the party can file an objection to the decision within 14 days of receipt. Interestingly, the second-instance authority cannot issue a decision complying with the party’s request, as no legal basis exists for executing a material and technical act via an administrative decision (Supreme Administrative Court in Lublin judgment of 20 June 2022, case no. II SA/Lu 507/02, Lex no. 738915).

It should be underlined that if the requested information is not public information, the body will only notify the applicant accordingly, but not issue a decision to deny access.

Entities obliged to provide public information

It may be surprising to learn that not just public bodies are obliged to provide public information, but also other entities that hold such information. Examples include a charitable organisation performing public tasks or a state-owned company disposing of public assets. But it must first be assessed whether an entity has the requested content and whether it is public information.

If the entity required to provide public information is not a public body, the Access to Public Information Act calls for the provisions discussed above to be applied as relevant. This means that if the entity refuses to make the information public or discontinues the proceeding involving the request, it will issue a decision that should retain the form of an administrative decision and ensure the possibility of reconsideration of the request by the addressee (Supreme Administrative Court judgments of 19 May 2017, case no. I OSK 2860/15, and 10 November 2017, I OSK 3312/15). Companies or foundations performing public tasks do not have an appellate body in the sense referred to in the Administrative Procedure Code, and therefore such a decision may be subject to a request for reconsideration, rather than an administrative appeal as in the case of public bodies. If the request is again denied, the applicant may file a complaint with the province administrative court.

Dominika Plewa-Rybacka, Dispute Resolution & Arbitration practice, Wardyński & Partners